The International Tinnitus Journal

Official Journal of the Neurootological and Equilibriometric Society

Official Journal of the Brazil Federal District Otorhinolaryngologist Society

ISSN: 0946-5448

Google scholar citation report

Citations : 12717

The International Tinnitus Journal received 12717 citations as per google scholar report

The International Tinnitus Journal peer review process verified at publons

Indexed In

- Excerpta Medica

- Scimago

- SCOPUS

- Publons

- EMBASE

- Google Scholar

- Euro Pub

- CAS Source Index (CASSI)

- Index Medicus

- Medline

- PubMed

- UGC

- EBSCO

Volume 29, Issue 1 / February 2025

Research Article Pages:11-16

10.5935/0946-5448.2025003

Can Pupillometry Help to Choose the Right Nerve for Tinnitus Reduction?

Authors:

Henk M. Koning

Abstract

Introduction: Tinnitus patients may suffer from autonomic symptoms, which can be measured with pupillometry. Objectives: This study was intended to assess the impact of pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) stimulation of cervical and cranial nerves (i.e. C2 nerve, auriculotemporal nerve, facial nerve and vagal nerve) on pupillometry measures in tinnitus patients. Design: A monocenter backward-looking group study. Results: The pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves gave in 40-60% of the patients a reduction of tinnitus with a 0-6% chance on side-effects. Postoperative basal pupil diameter, maximum constriction amplitude, and maximum constriction velocity were statistically significant between the various treatments. PRF of the trigeminocervical nerves had little parasympathetic and sympathetic effects in contrast to the impairment of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system induced by PRF of the facial and vagal nerves. Conclusions: The results of PRF with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves on tinnitus were not related to postoperative parasympathetic measurements.

Keywords:

Tinnitus, Pulsed radiofrequency, C2 nerve, Auriculotemporal nerve, Facial nerve, Vagal nerve, Pupillometry, Autonomic nervous system.

Keywords

Tinnitus, Pulsed radiofrequency, C2 nerve, Auriculotemporal nerve, Facial nerve, Vagal nerve, Pupillometry,

Autonomic nervous system.

Introduction

Tinnitus patients may suffer from autonomic symptoms, which can be measured with pupillometry [1]. Baseline pupil diameter (BPD), maximum constriction amplitude (MCA), and maximum constriction velocity (MCV) were significantly reduced in tinnitus patients, and this might indicate parasympathetic dysfunction. The relation between noradrenergic locus coeruleus (LC) neurons and pupil size is due to the control exerted by the LC on the preganglionic parasympathetic neurons of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, which innervate the iris constrictor [2]. The amygdala and LC state actively determines which sensory signals are selected for processing in sensory brain regions and may function as a gate to filter out unwanted sound such as tinnitus [3].

Electric stimulation of the cervical and cranial nerves can suppress tinnitus [4,5]. The challenge is how to match electric stimulation of a specific nerve to the type of tinnitus in order to achieve a successful therapy [6]. Especially, tinnitus related to the autonomic nervous system could benefit from stimulation of cervical or cranial nerves connected to the autonomic nervous system [1]. The vagal nerve is considered as a mediator of the parasympathetic section of the autonomic nervous system [7]. The facial nerve is also partially composed of parasympathetic neurons [8]. The trigeminal nerve does not have parasympathetic fibres, but it is associated with several parasympathetic ganglia along its course [9]. The first cervical roots are intensely connected to the trigeminal system [10]. Therefore, this study was intended to assess the impact of Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF) stimulation of these cervical and cranial nerves on pupillometry measures in tinnitus patients.

Methods

Design

This observational retrospective study in Pain Clinic De Bilt, De Bilt, the Netherlands, comprises all tinnitus patients who underwent pupillometry and pulsed radiofrequency therapy with 42 volts in Pain Clinic De Bilt between October 2023 and October 2024 (n = 52). The Ethics Committee United (Nieuwegein, the Netherlands) acknowledged this study (W.25.001, January 8, 2025).

Subjects

All tinnitus patients subjected to pupillometry and treated with pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of C2 dorsal root ganglion, the auricular branch of the vagal nerve, the auriculotemporal nerve, or the facial nerve in the period between October 2023 and October 2024. The work-up of a patient with tinnitus comprised of a clinical history, a two-sided clinical audiogram, a cervical spine radiograph and pupillometry. The pupillometer was applied in all patients to both eyes.

Outcome

The prime outcomes were subjective change in tinnitus loudness at 7 weeks post treatment.

Adverse effects

Side effects were registered directly after and at 7 weeks post treatment.

Quantitative Pupillometry

Pupillometry were executed using an automated pupillometer (NeuroLight Algiscan, ID-MED, Marseille, France). An assessment before therapy, and an assessment after therapy were performed for each eye of the patient. The following parameters were obtained: baseline pupil diameter (BPD) (mm), latency of constriction (LC) (msec), pupillary constriction rate (i.e., the difference between baseline and post-stimulation pupil size, expressed as % of constriction from the baseline value) (PCR), maximum constriction amplitude (MCA) (mm), and maximal constriction velocity (MCV) (mm/sec).

Pulsed radiofrequency therapy with 42 volts

The auricular branch of the vagal nerve. A 22-gauge, 60 mm long needle with a 5 mm active tip was positioned percutaneously at the inner tragus. Then, pulsed radiofrequency was applied at 42 V, 2 Hz, and 10 milliseconds for 10 minutes.

The auriculotemporal nerve. A 22-gauge, 60 mm-long needle with a 5 mm active tip was put in about 6 millimetres in front of the joining of the tragus and the earlobe, posteriorly to the mandible. The needle was advanced superior into the subcondylar area to a depth of about 25-28 millimetre. Then PRF at 42 V, 2 Hz, and 10 milliseconds for 10 minutes was applied.

The C2 dorsal root ganglion. The procedure took place by utilizing a C-arm fluo¬roscopic machine. The patient was placed in the prone position on the fluoroscopic table. The atlanto-occipital joint to be treated was marked in the anteroposterior view. A 22-gauge, 100 mm-long needle with a 5 mm active tip was placed and directed toward the posterolateral aspect of the atlanto-occipital joint. The C-arm was rotated to the horizontal plane and the needle were then advanced between C1 and C2 until bone contact was made. After confirmation of correct needle placement, the C2 ganglion was subjected to pulsed radiofrequency at 42 V, 2 Hz, and 10 milliseconds for 120 seconds.

The facial nerve. A 22-gauge, 60 mm-long needle with a 5 mm active tip was put in the middle of the posterior boundary of the mandibular ramus and the frontier border of the mastoid process, just atop of the lowest end of the earlobe. Then, the needle was preceded for 20-25 mm to the expected stylomastoid foramen. After aspiration for blood, PRF at 42 V, 2 Hz, and 10 milliseconds for 10 minutes was administered.

Data Assessment

The information obtained included clinical information and data of the quantitative pupillometry.

Statistical Methods

Data were explored with Minitab 18 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA) using Student’s t-test, and χ2 test. Analysis of variance was used to differentiate between the groups of tinnitus patients treated with pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of C2 dorsal root ganglion, the auricular branch of the vagal nerve, the auriculotemporal nerve, or the facial nerve. A P-value smaller than 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

In a one-year period, 57 tinnitus patients underwent pupillometry and a pulsed radiofrequency therapy with 42 volts (Table 1). Displays the clinical parameters of the patients. The results and side-effects of therapy are shown in (Table 2). The pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of various nerves gave in 40-60% of the patients a reduction of tinnitus with a 0-6% chance on side-effects. There was no statistical difference in the results between the various nerves.

| Prevalence | Median | Q1 – Q3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 56 | 48 – 66 | |

| Gender (male) | 66% | ||

| Hearing loss (dB) at: | |||

| 250 Hz | 10 | 5 – 20 | |

| 500 Hz | 10 | 5 – 25 | |

| 1 kHz | 15 | 5 – 29 | |

| 2 kHz | 15 | 5 – 30 | |

| 4 kHz | 25 | 15 – 49 | |

| 8 kHz | 40 | 15 – 60 | |

| Pupillometry pre-operative | |||

| BPD (mm) | 3.8 | 3.3 – 4.4 | |

| MCA (mm) | 1.1 | 0.8 – 1.3 | |

| MCV (mm/sec) | 3.2 | 2.3 – 3.8 | |

Table 1: Clinical Characteristics of the patients with tinnitus.

| Vagal nerve ( n=22) | Facial nerve (n=16) | Auriculotemporal nerve (n=9) | Ganglion C2 (n=5) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive effect of therapy | 41% | 44% | 56% | 60% | 0.525 |

| Moderate to good effect | 32% | 38% | 44% | 60% | 0.323 |

| Side-effects | 5% Increase of tinnitus | 6% Leg cramps | 0% | 0% | 0.651 |

Table 2: Results and side-effects of PRF of various nerves on tinnitus.

The effects of pulsed radiofrequency therapy of various nerves on pupillometry are shown in (Table 3). Postoperative BPD, MCA and MCV were statistically significant between the various treatments. PRF of the vagal nerve and the facial nerve induced a lower MCV than the PRF of the auriculotemporal nerve and the C2 dorsal root ganglion.

| Vagal nerve (n=43) | Facial nerve (n=32) | Auriculotemporal nerve (n=18) | Ganglion C2 (n=10) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||||

| BPD (mm) | 3.9 0.86 | 3.6 0.77 | 4.2 0.54 | 4.2 0.85 | 0.05 |

| MCA (mm) | 1.2 0.67 | 1.0 0.55 | 1.1 0.29 | 1.1 0.29 | 0.305 |

| MCV (mm/s) | 3.5 1.83 | 3.2 2.90 | 3.8 1.88 | 3.1 1.06 | 0.767 |

| Postoperative | |||||

| BPD (mm) | 3.7 1.00 | 3.4 0.41 | 4.2 0.56 | 3.7 0.34 | 0.005 |

| MCA (mm) | 1.0 0.40 | 0.8 0.46 | 1.2 0.37 | 0.9 0.29 | 0.023 |

| MCV(mm/s) | 2.9 1.25 | 2.5 0.67 | 3.9 1.01 | 3.2 0.56 | 0 |

| Difference | |||||

| BPD (mm) | -0.2 0.69 | -0.3 0.63 | -0.1 0.30 | -0.5 0.78 | 0.447 |

| MCA (mm) | -0.2 0.64 | -0.2 0.49 | 0.0 0.30 | -0.1 0.34 | 0.327 |

| MCV (mm/s) | -0.6 1.60 | -0.7 2.57 | 0.1 1.55 | 0.2 0.81 | 0.408 |

Table 3: The pupillometric effects of pulsed radiofrequency therapy of various nerves.

The trigeminocervical complex consist of the trigeminal and the cervical dorsal root ganglia. The pupillometry of these nerves were compared with the pupillometry of the facial and vagal nerves (Table 4). Pulsed radiofrequency of the trigeminocervical nerves induced a statistically significant higher postoperative BPD, MCA, and MCV compared to the facial and vagal nerves and less impairment in the difference between the pre- and postoperative MCA and MCV. This might indicate that PRF of the trigeminocervical nerves had little parasympathetic and sympathetic effects in contrast to the impairment of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system induced by PRF of the facial and vagal nerves.

| PRF of ganglion C2 or auriculotemporal nerve (n=28) | PRF of the facial or the vagal nerve (n=75) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||

| BPD (mm) | 4.2 0.65 | 3.8 0.83 | 0.008 |

| MCA (mm) | 1.1 0.28 | 1.1 0.64 | 0.85 |

| MCV (mm/s) | 3.5 1.65 | 3.4 2.33 | 0.668 |

| Postoperative | |||

| BPD (mm) | 4.0 0.53 | 3.6 0.81 | 0.002 |

| MCA (mm) | 1.1 0.36 | 0.9 0.44 | 0.036 |

| MCV (mm/s) | 3.6 0.92 | 2.7 1.05 | 0 |

| Difference | |||

| BPD (mm) | -0.2 0.54 | -0.2 0.66 | 0.848 |

| MCA (mm) | 0.0 0.31 | -0.2 0.58 | 0.029 |

| MCV (mm/s) | 0.1 1.32 | -0.6 2.06 | 0.042 |

Table 4: The pupillometric effects of pulsed radiofrequency therapy of the nerves of the trigeminocervical complex compared with pulsed radiofrequency therapy of the facial and vagal nerves.

There is a statistical significant difference in postoperative MCA for the PRF of the various nerves, but the postoperative MCA was not related to the results of therapy (Table 5). There was also a statistical significant difference in postoperative MCA when the PRF of the trigeminocervical nerves was compared to the PRF of the facial and vagal nerves (Table 6). However, the success of therapy was not related to the postoperative MCA.

| Postoperative MCA (mm) | Beneficial result of PRF | No effect of PRF | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vagal nerve | 1.0 0.40 | 1.0 0.30 | 0.9 0.46 | 0.405 |

| Facial nerve | 0.8 0.46 | 0.8 0.22 | 0.7 0.29 | 0.06 |

| Auriculotemporal nerve | 1.2 0.37 | 1.3 0.24 | 1.1 0.33 | 0.148 |

| Ganglion C2 | 0.9 0.29 | 1.0 0.13 | 1.0 0.32 | 0.976 |

| p-value | 0.023 |

Table 5: Postoperative MCA following PRF of the various nerves and the relation to a successful result of therapy.

| Postoperative MCA (mm) | Beneficial result of PRF | No effect of PRF | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRF of ganglion C2 or auriculotemporal nerve | 1.1 0.36 | 1.2 0.34 | 1.0 0.37 | 0.214 |

| PRF of the facial or the vagal nerve | 0.9 0.44 | 1.0 0.44 | 0.8 0.42 | 0.066 |

| p-value | 0.036 |

Table 6: Postoperative MCA following PRF of the nerves of the trigeminocervical complex compared with pulsed radiofrequency therapy of the facial and vagal nerves and the relation to a successful result of therapy.

Discussion

The pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves gave in 40-60% of the patients a reduction of tinnitus with a 0-6% chance on side-effects. Postoperative BPD, MCA and MCV were statistically significant between the various treatments. PRF of the trigeminocervical nerves had little parasympathetic and sympathetic effects in contrast to the impairment of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system induced by PRF of the facial and vagal nerves. The results of pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves on tinnitus were not related to postoperative parasympathetic measurements.

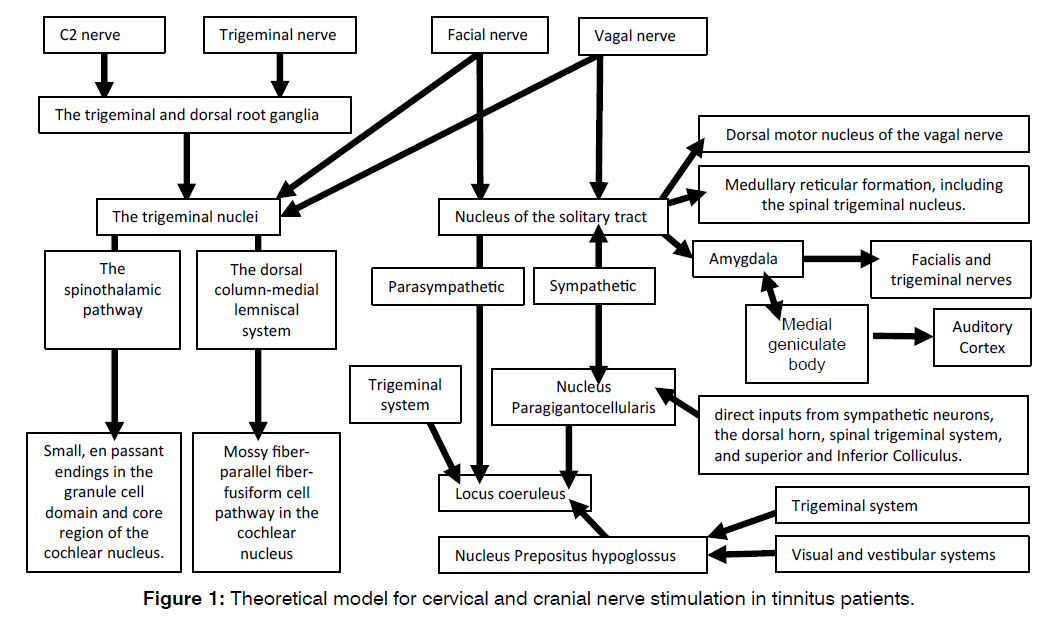

Tinnitus is thought to arise from aberrant neural activity within central auditory pathways that may be influenced by multiple brain centres, including the somatosensory system [11]. The cochlear nucleus is the central site for multisensory integration of inputs originating in sources other than the auditory nerve, namely, somatosensory inputs from the trigeminal ganglia, cervical dorsal root ganglia, spinal trigeminal nucleus, and dorsal column nuclei [12]. Mossy fibres from the spinal trigeminal and dorsal column nuclei end in the granule cell domain [13]. En passant boutons from the trigeminal and cervical ganglia innervate the granule cell domain and also the core region of the cochlear nucleus. Also, the lateral reticular formation, which receives projections from diverse brain stem pathways and the spinal cord, projects to the granule cell domain of the cochlear nucleus [14].

Electric stimulation of the cervical and cranial nerves can suppress tinnitus [4,5]. The challenge is to find out which nerve can be used for each type of tinnitus. Tinnitus patients may suffer from parasympathetic dysfunction, which can be measured with pupillometry [1]. Especially BPD and MCA, measured with pupillometry, are reliable measures associated with the outcome of vagal nerve stimulation in patients with tinnitus [15]. Despite the close relationship between BPD and LC activity, the mechanisms underlying this relationship are not yet fully understood. Also, the influence of PRF of the various cervical and cranial nerves on pupillometry is unknown and this can provide us with further knowledge in the therapy of tinnitus.

The first cervical roots are intensely connected to the trigeminal system [10]. Somatosensory input to the cervical and trigeminal ganglia is transmitted directly and indirectly through second order nuclei to the ventral and dorsal cochlear nucleus (VCN, DCN) and to the inferior colliculus [14]. The apical dendrites of fusiform cells are activated through stimulation of the trigeminal or the C2 ganglion [16]. The C2 ganglion also projects to the primary dendrites of unipolar brush cells, and the distal dendrites of granule cells [13]. In our study, in patients with PRF of the C2 ganglion the BPD decreased and the MCA and MCV remained the same. We concluded that PRF of the ganglion C2 did not impair the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system.

Either the ophthalmic division or the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve are used for electrical stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion [13,14]. The trigeminal tract in the brainstem does not receive just afferents from the trigeminal ganglion, but also from other nerves such as vagal and nerves from the upper cervical segments [17]. Trigeminal sensory nuclei project bilaterally to multiple nearby brainstem nuclei, including the nucleus tractus solitarius, the locus coeruleus and the dorsal raphe nucleus [18]. Stimulation of the trigeminal nerve produces neuronal excitation in the VCN, and a complex mixture of excitation and inhibition in the DCN [19]. The C2 pathway mostly inhibits and the trigeminal pathway mostly excites neurons in the DCN [14]. The localization and response characteristics of these units upon stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion are consistent with those of the fusiform or giant cells in the DCN and bushy or stellate cells in the VCN [20]. In our study, patients with PRF of the trigeminal nerve did not change the postoperative BPD, MCA and MCV considerably and we concluded that PRF of the trigeminal ganglion did not influence the autonomic nervous system.

Vagal nerve stimulation is an effective and safe method for reducing tinnitus [21]. The vagal nerve innervates the nucleus tractus solitarius, which sends excitatory projections to the LC via the nucleus paragigantocellularis, and to the caudal ventrolateral medulla [22,23]. The caudal ventrolateral medulla inhibits the rostroventrolateral medulla, which in their turn excites the sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord. This inhibition would decrease sympathetic activity. Locus coeruleus neurons also project to the cochlear nucleus and to the auditory cortex, inhibiting the spontaneous firing of the neurons [24]. The network of vagal nerve stimulation activates also the trigeminal brainstem nuclei and the nucleus cuneatus and a direct effect on the cochlear nucleus could also a possible mechanism of action in tinnitus patients [9]. In our study, patients with PRF of the vagal nerve did impair the postoperative BPD, MCA and MCV considerably although it did not reach statistical significance.

The facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagal nerves do not have their own sensory brainstem nuclei but convey their somatosensory information to the brainstem nuclei of the trigeminal nerve [9]. The facial nerve is also partially composed of parasympathetic neurons [8]. In our study, PRF of the facial nerve did impair the postoperative BPD, MCA and MCV considerably although it did not reach statistical significance.

The results of pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves on tinnitus were not related to postoperative parasympathetic measurements. Also, all the cervical and cranial nerves treated with PRF for tinnitus were connected to the cochlear nucleus and also to the locus coeruleus (Figure 1). Therefore, it is a hard to make a distinction between the roles of the cochlear nucleus or the locus coeruleus in the mechanisms of action of PRF of the cervical and cranial nerves. Because of the lack of correlation between parasympathetic measurements and the effect of therapy, we suggest that the most likely site of action of PRF of cervical and cranial nerves in tinnitus is the cochlear nucleus.

Figure 1: Theoretical model for cervical and cranial nerve stimulation in tinnitus patients.

Small sample size was the major limitation of this study. The statements in our study are limited owing to its backward-looking quality and a prospective investigation with a larger number of patients is advised to affirm the outcome and our interpretations.

Conclusion

This study was intended to assess the impact of pulsed radiofrequency stimulation of cervical and cranial nerves on pupillometry measures. The pulsed radiofrequency with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves gave in 40-60% of the patients a reduction of tinnitus with a 0-6% chance on side-effects. Postoperative BPD, MCA and MCV were statistically significant between the various treatments. PRF of the trigeminocervical nerves had little parasympathetic and sympathetic effects in contrast to the impairment of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system induced by PRF of the facial and vagal nerves. The results of PRF with 42 volts of various cervical and cranial nerves on tinnitus were not related to postoperative parasympathetic measurements. Because of the lack of correlation between parasympathetic measurements and the effect of therapy, we suggest that the most likely site of action of PRF of cervical and cranial nerves in tinnitus is the cochlear nucleus.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tuinebreijer WE, Koning HM. Association between Anterior Cervical Osteophytes and Parasympathetic Dysfunction in Tinnitus Patients. Int Tinnitus J. 2024;28(1):70-6.

- De Cicco V, Tramonti Fantozzi MP, Cataldo E, Barresi M, Bruschini L, Faraguna U, et al. Trigeminal, visceral and vestibular inputs may improve cognitive functions by acting through the locus coeruleus and the ascending reticular activating system: a new hypothesis. Front Neuroanat. 2018;11:130.

- Fast CD, McGann JP. Amygdalar gating of early sensory processing through interactions with locus coeruleus. Neurosci J. 2017;37(11):3085-101.

- Hoare DJ, Adjamian P, Sereda M. Electrical stimulation of the ear, head, cranial nerve, or cortex for the treatment of tinnitus: a scoping review. Neural Plast. 2016;2016(1):5130503.

- Yakunina N, Nam EC. Direct and transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of tinnitus: a scoping review. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:680590.

- Zeng FG, Djalilian H, Lin H. Tinnitus treatment with precise and optimal electric stimulation: opportunities and challenges. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;23(5):382-7.

- Kaniusas E, Kampusch S, Tittgemeyer M, Panetsos F, Gines RF, Papa M, et al. Current directions in the auricular vagus nerve stimulation I–a physiological perspective. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:854.

- Fanara B, Lambiel S. Effect of auricular acupuncture on propofol induction dose: Could vagus nerve and parasympathetic stimulation replace intravenous co-induction agents?. Med Acupunct. 2019;31(2):103-8.

- Cakmak YO. Concerning auricular vagal nerve stimulation: occult neural networks. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:421.

- Edvinsson JC, Viganò A, Alekseeva A, Alieva E, Arruda R, De Luca C, et al. The fifth cranial nerve in headaches. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:1-7.

- Basura GJ, Koehler SD, Shore SE. Multi-sensory integration in brainstem and auditory cortex. Brain Res J. 2012;1485:95-107.

- Cheng YF, Xirasagar S, Yang TH, Wu CS, Kao YW, Shia BC, et al. Increased risk of tinnitus following a trigeminal neuralgia diagnosis: A one-year follow-up study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:1-7.

- Shore S, Zhou J, Koehler S. Neural mechanisms underlying somatic tinnitus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:107-548.

- Dehmel S, Cui YL, Shore SE. Cross-modal interactions of auditory and somatic inputs in the brainstem and midbrain and their imbalance in tinnitus and deafness. Am J Audiol. 2008;17(2):S193-209.

- Koning HM, Tuinebreijer WE. Exploring the Novel Impact of Vagal Nerve Stimulation on Pupillometry Measures in Tinnitus Patients. Int Tinnitus J. 2024;28(2):216-22.

- Martel DT, Pardo-Garcia TR, Shore SE. Dorsal cochlear nucleus fusiform-cell plasticity is altered in salicylate-induced tinnitus. Neurosci J. 2019;407:170-81.

- Bicanic I, Hladnik A, Džaja D, Petanjek Z. Anatomija orofacijalne inervacije. Acta Clin Croat. 2019;58(Supplement 1):35-41.

- Mercante B, Ginatempo F, Manca A, Melis F, Enrico P, Deriu F. Anatomo-physiologic basis for auricular stimulation. Med Acupunct. 2018;30(3):141-50.

- Soleymani T, Pieton D, Pezeshkian P, Miller P, Gorgulho AA, Pouratian N, et al. Surgical approaches to tinnitus treatment: A review and novel approaches. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:154.

- Ralli M, Greco A, Turchetta R, Altissimi G, de Vincentiis M, Cianfrone G. Somatosensory tinnitus: Current evidence and future perspectives. Int J Med Res. 2017;45(3):933-47.

- Li TT, Wang ZJ, Yang SB, Zhu JH, Zhang SZ, Cai SJ, et al. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation at auricular acupoints innervated by auricular branch of vagus nerve pairing tone for tinnitus: study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Trials J. 2015;16:1-9.

- Berger A, Vespa S, Dricot L, Dumoulin M, Vandewalle G, El Tahry R. How is the norepinephrine system involved in the antiepileptic effects of vagus nerve stimulation?. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:790943.

- Butt MF, Albusoda A, Farmer AD, Aziz Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J Anat. 2020;236(4):588-611.

- Martins AR, Froemke RC. Coordinated forms of noradrenergic plasticity in the locus coeruleus and primary auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(10):1483-92.

Department of Pain therapy, Pain Clinic De Bilt, De Bilt, The Netherlands

Send correspondence to:

H.M. Koning

Department of Pain therapy, Pain Clinic De Bilt, De Bilt, The Netherlands, Tel: 0031302040753, E-mail: hmkoning@pijnkliniekdebilt.nl

Paper submitted on January 10, 2024; and Accepted on Jan 30, 2024

Citation: Henk M. Koning. Can Pupillometry Help to Choose the Right Nerve for Tinnitus Reduction?. Int Tinnitus J. 2024;29(1): 11-16.