The International Tinnitus Journal

Official Journal of the Neurootological and Equilibriometric Society

Official Journal of the Brazil Federal District Otorhinolaryngologist Society

ISSN: 0946-5448

Google scholar citation report

Citations : 12717

The International Tinnitus Journal received 12717 citations as per google scholar report

The International Tinnitus Journal peer review process verified at publons

Indexed In

- Excerpta Medica

- Scimago

- SCOPUS

- Publons

- EMBASE

- Google Scholar

- Euro Pub

- CAS Source Index (CASSI)

- Index Medicus

- Medline

- PubMed

- UGC

- EBSCO

Volume 23, Issue 2 / August 2019

Review Article Pages:79-85

Hearing loss and Alzheimer?s disease: A Review

Authors: Massimo Ralli, Antonio Gilardi, Arianna Di Stadio, Cinzia Severini, Antonio Greco, Marco de Vincentiis,Francesco Salzano

PDF

Abstract

Many studies have focused on the relationship between hearing loss and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The mechanisms and causal relationship of this association are still partially unknown, and several theories have been proposed. The most accredited hypothesis is that peripheral hearing deprivation may lead to social isolation and subsequently to dementia. Another hypothesis supports the role of hearing loss on cortical processing, with an increased assignment of cognitive resources to auditory processing rather than to other cognitive processes; other theories suggest changes in the brain structure following reduced peripheral auditory stimulation, or a common cause to both conditions. These preliminary findings clearly delineate the importance of further research aimed at investigating hearing impairment in AD, to a) allow early detection of people with predisposition to AD, b) improve the quality of life in AD patients with hearing loss and c) possibly prevent the progression of the disease treating the hearing impairment. In this review paper, the authors discuss current evidence on the association between hearing impairment and dementia, the identification of peripheral and central auditory dysfunction in at-risk patients as a potential early indicator of incipient AD, and the clinical aspects and the management of patients with AD and hearing loss

Keywords: Alzheimerâs disease; hearing loss; Presbycusis; dementia

Introduction

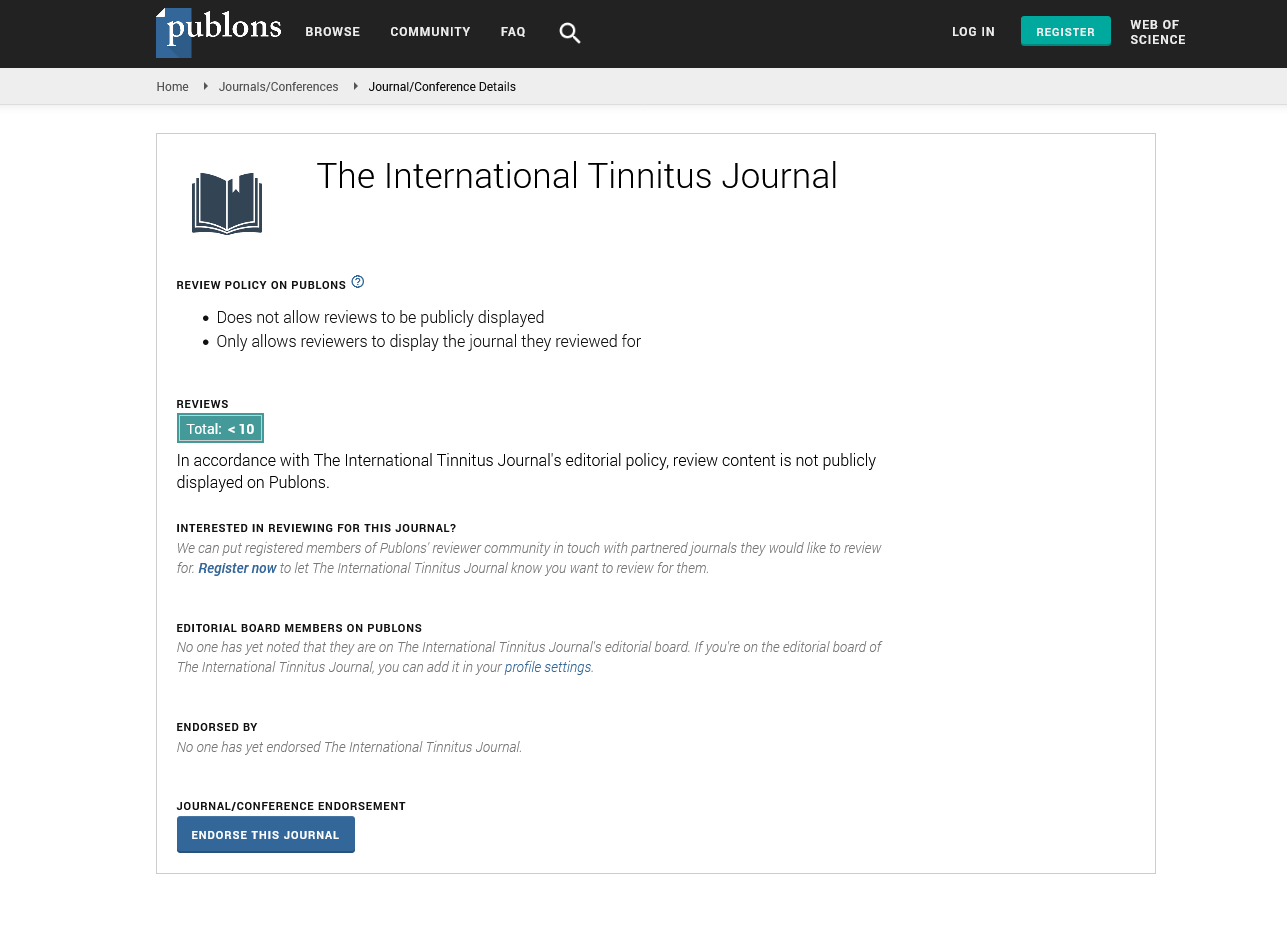

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is an acquired condition characterized by progressive cognitive and behavioural decline and is the second most common form of dementia in the general population after mild cognitive impairment[1]. It is estimated that approximately 20 million people worldwide are affected from AD; however, only a portion of them is correctly diagnosed[2-4]. In the United States, around 5.5 million people have AD of these, most (nearly 5.3 million) are 65 year old and older while only 200.000 have a young-onset form of AD[5]. The National Institute on Aging indicated that the prevalence of AD doubles every five years beyond the age of 65[6] therefore, as the population ages, AD impacts a greater percentage of people. It has been hypothesized that the total number of individuals with AD in the United States could increase to as high as 16 million by 2050[7,8]. The correct identification of AD risk factors can be helpful in intercepting the disease and slowing its progression. At the moment, it is well known that age, family history, and biological inheritance are risk factors for AD[4] however these factors cannot be modified and, thus, cannot contribute to reduce disease progression. The identification of other possibly modifiable risk factors may therefore help in the management of patients with AD. Aging is the most prevalent cause of sensorineural hearing loss[9]. The presence of hearing loss in the elderly is described by the term “presbycusis” it typically presents as sensorineural hearing loss characterized by loss in the high frequencies[10] (Figure 1) and sometimes may be associated to the presence of cochlear dead regions[11]. Presbycusis, the second most common health issue of the aged population after arthritis[12], may present as a multifactorial hearing disorder characterized not only by general hearing disability, but also impaired recognition of words, especially in noisy environments, tinnitus and hyperacusis[13-15]. Recent studies have also suggested a role of synaptopathy between inner hair cells and sensory neurons in presbycusis[16-18]. The ability to communicate with friends and family mainly depends on one’s ability to hear and process speech and environmental sounds. When individuals develop presbycusis, they are hampered in their ability to converse by phone or face to face; these problems often have a significant impact on social life and may favor the onset of depression, cognitive decline and dementia[19]. Epidemiological studies have described an association between hearing loss and cognitive impairment including AD other studies have shown that hearing disorders may be a potentially modifiable risk factor of AD[20-25]. In a review published in 2018, Swords et al.[26] reported that both peripheral and central auditory system alterations can be found in early AD stages and they could be early indicators of the disease, thus suggesting to investigate peripheral and central auditory dysfunction in at-risk subjects as this could be an effective strategy to diagnose AD in its early stages and initiate therapeutic interventions aimed at enhancing the quality of life of AD patients and hopefully have a role in disease progression. These preliminary findings clearly delineate the importance of further research aimed at investigating hearing impairment in AD, to a) allow early detection of people with predisposition to AD, b) improve the quality of life in AD patients with hearing loss and c) possibly prevent the progression of the disease treating the hearing impairment.

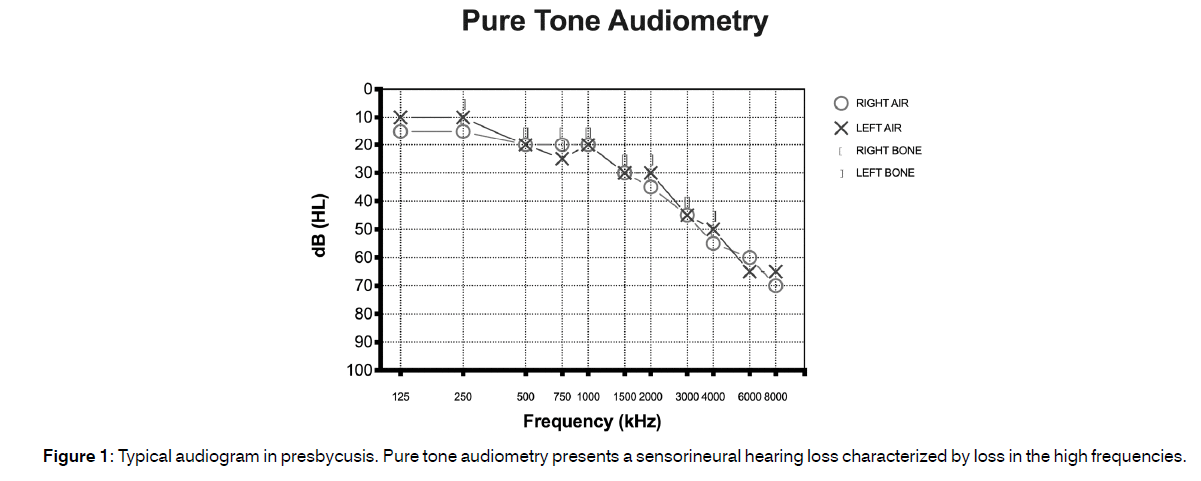

Association between hearing loss and Alzheimer’s disease

Hearing loss and AD are common conditions in older adults with a significant impact on quality of life[24-27]. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a correlation between these conditions and the role of hearing loss as a modifiable risk factor for the development of AD (20- 26). An observation study conducted by Uhlmann et al.[28] in 1986 on 156 patients with AD suggested hearing loss being an indicator for the development of cognitive dysfunction. A few years later, the same authors confirmed these preliminary findings reporting that hearing loss was significantly and independently correlated with the severity of cognitive dysfunction in an AD case-control study matched for age, sex, and education status[29]. Since then, several studies confirmed the association between AD and hearing impairment; however, the physiopathological mechanisms and causal relationship of this association remain unknown[30]. There are several theories that support the correlation between hearing loss and AD[31]. The most accredited hypothesis is that hearing impairment may lead to sensory deprivation and social isolation that subsequently leads to dementia[32-35]. Another theory suggests that hearing loss may affect cortical processing through the increase of the cognitive load and the assignment of cognitive resources to auditory processing rather than to other cognitive processes[36-38]. This hypothesis is also based on the evidence that auditory processing needs more cognitive resources when the auditory signal is deteriorated, thus resulting in the degradation of other cognitive processes[39]. Another theory proposes that decreased auditory stimulation causes changes in brain structure making the brain more vulnerable to factors able to cause brain pathologies, such as neurofibrillary tangles, Aβ accumulation, and micro-vascular disease, thus leading to a higher risk of dementia[40]. Other studies have speculated that there may be a common cause to both diseases and therefore hearing loss may be an early symptom of dementia; in fact, the auditory and the memory areas are strictly related and an atrophy in one of the two may impact on the other (Figure 2)[26-42]. Chang et al.[43] attempted to discover the mechanisms underlying this association using animal models to elucidate the time course of cognitive decline following hearing loss and then evaluating changes in cognitive function and synaptic protein levels after induction of the hearing loss. They found that degeneration in the central auditory pathways may cause the degeneration of the synapses of hippocampus or increase the vulnerability of these synapses to damage. This hypothesis is supported by findings showing that focal cortical infarction of brain regions that are remote but connected to the hippocampus can induce neuronal loss in the hippocampus.

It has examined the involvement of a molecular pathway underlying the association between hearing loss and AD[44]. The authors summarized the enzymes and proteins that may have a role in the pathogenesis of both agerelated hearing loss and AD and suggested that an abnormal expression of these structures, including Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), SIRT1- PGC1α, and LKB1 (or CaMKKβ)-AMPK, may cause both AD and dysfunction of cochlear hair cells[45-50]. In addition, they hypothesized that these two conditions may also influence the progression of each other as they have common pathological pathways and targets. Although a large number of studies have investigated this relationship, there is still controversy about the role of peripheral hearing impairment and central auditory processing in AD. Peripheral hearing loss might have a more direct role on neurodegenerative processes at the base of dementia. In fact, hearing loss in older adults positively correlates with reduction of tissue volume in auditory cortex, temporal lobe, and the whole brain, and may lead to functional reorganization of auditory cortical networks[20-32]. The role of the central auditory processing in AD is still not well understood. Alterations in central auditory processing may reflect abnormal cortical mechanisms employed in the analysis of auditory scenes this is supported by the evidence that even minor alterations in auditory cortical evoked potentials can precede clinical symptoms of the neurological condition in young patients with pathogenic AD mutations[19-54]. A recent systematic review from Thomson et al.[31] included 17 articles that indicate an association between hearing loss and dementia or cognitive decline, although a large variation in the methods used for ascertaining hearing loss and dementia was present in the included articles. Hearing loss was mainly evaluated through the peripheral auditory function with Pure Tone Audiometry (PTA), while only a fraction of the included studies measured central auditory function. Dementia was mainly defined using the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE). The authors concluded that although they found a significant variability in the methods used to evaluate patients in the included studies, and they mainly evaluated peripheral hearing loss, each of them demonstrated that hearing loss was associated with higher incidence of dementia in older adults.

Results of other studies instead reported almost-normal pure tone thresholds in patients with AD, thus suggesting that AD pathology may be mainly associated with central, rather than peripheral, auditory dysfunction. Central auditory dysfunction should be suspected in subjects that report difficulties in understanding speech in background noise[16]. Gates et al.[52] reported central auditory dysfunction as a prelude of AD performing central auditory processing tests in 274 elderly subjects with a mean age of 79.6 years and monitored them for a period of four years. The authors found that the results of central auditory processing tests were significantly worse in the patients that developed dementia during follow up and recommended to evaluate central auditory function in seniors complaining of hearing difficulty and in those specifically reporting difficulties in hearing in noise. Another study on patients in the Framingham dementia cohort55, found that severe central auditory dysfunction, based on low scores on the Synthetic Sentence Identification with Ipsilateral Competing Message test, could be an indicator of dementia diagnosis within 3 to 12 years. In support of these hypotheses, a magnetic resonance brain image study by Lin et al.[40] indicated that hearing loss is correlated with atrophy of the whole brain; such changes were more evident in the right temporal lobe.

Clinical features of hearing loss in Alzheimer’s disease

Hearing impairment in AD does not have specific characteristics that differentiate it from age-related hearing loss or from other forms of sensorineural hearing impairment; however, certain evidence suggests auditory cognitive disorders in AD[19]. It has been reported that patients with AD may experience more listening difficulties than expected from the degree of hearing loss diagnosed with PTA and may have a reduced benefit from the use of hearing aids[56-59]. Commonly, AD patients report difficulties in listening and in understanding the meaning of words in the presence of background noise; this contributes to the avoidance of social environments. However, this condition may also be present in otherwise healthy older adults with presbycusis[60]. Furthermore, patients with AD may have various abnormal behavioral responses to sounds, with an alteration in the mechanisms of matching sounds with past experiences[61] leading to a poor or an aberrant perception of sounds. The first case constitutes an auditory agnosia, which consists in the impairment in sound perception and identification despite intact hearing, and may be limited to specific sounds, while the second may manifest as auditory hallucinations most probably deriving from aberrant cortical activity[62]. Last, hyperacusis the intolerance to certain everyday sounds that cause significant distress and impairment in daily activities[63,64] has been also reported in patients with AD[65].

Clinical management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and hearing loss

A symptom-based clinical approach to patients presenting with cognitive impairment and hearing loss has been proposed by Hardy et al.[19]. The authors suggested that the assessment of hearing loss in patients with a neurological diagnosis of dementia, including AD, should initiate with clinical history evaluation to highlight key auditory symptoms, followed by a complete audio logical and neurological examination. Audio logical evaluation should include PTA, oto-acoustic emissions and brainstem auditory evoked potentials. Additional auditory tests, such as measurement of speech in noise perception, gap-in-noise perception, dichotic listening and tone-in noise audiometry[66,67] can be used as they more closely reflects “real world” hearing impairment and may indicate alterations in cortical auditory processing. At this regard, Rahman et al.[68] evaluated central auditory processing in 150 patients with a neurological diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and compared the results to 150 age, sex and PTA-matched controls; the authors used selective auditory attention test, auditory fusion test, pitch pattern sequences test, and dichotic digits test and found a significant alteration of central auditory processing test scores in patients in the study group compared to those in the control group. General neuropsychological assessment should then be performed to identify executive or attention deficits that can also be present in these patients and may confound the results of auditory tests. Diagnosis should always include brain magnetic resonance imaging to exclude concurrent retrocochlear conditions i.e. vestibular schwannoma[69,70] and further characterize the neuroanatomical basis of the auditory deficit[19]. The management of patients with AD and hearing loss requires a multidisciplinary approach by audiologists, speech and language therapists, and neurologists and should include the immediate correction of any treatable cause of hearing impairment, such as the removal of earwax[71,72], the use of hearing aids and other listening devices and specific strategies such as the employment of written communication and electronic devices, the reduction of background noise, the avoidance of subjective distressing sounds and the use of competing techniques for auditory hallucinations[73].

Conclusion

Much evidence has accumulated in the past decades on the association between hearing loss and AD however the underlying mechanisms of this association remain partly unclear. Large-scale studies that employ on one side comprehensive peripheral and central hearing function evaluation and on the other a rigorous evaluation of AD diagnosis and brain magnetic resonance imaging are necessary to robustly assess the association of hearing impairment and AD. Furthermore, the understanding of the mechanisms underlying this association is still partial and requires specifically-aimed study protocols. Recent studies have shown a correlation between hearing loss and changes in brain structures of animal models that, together with changes in the molecular pathway at the base of these pathologies, could carry forward the future of research in this field. In fact, the identification of potentially common targets or pathways could allow the development of drugs aimed at this common target. On a clinical perspective, the correct identification of hearing loss in patients with AD is crucial, as its treatment has been shown to significantly improve the global condition of these patients. The management of patients with AD and hearing loss requires a multidisciplinary approach that should include audiologists, speech and language therapists, and neurologists.

Conflicts of Interest

The Author declares no potential conflict of interest on publishing this paper.

References

- Warren JD, Fletcher PD, Golden HL. The paradox of syndromic diversity in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:451-64.

- Group GBDNDC. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:877-97.

- Niu H, Alvarez AI, Guillen GF, Aguinaga OI. Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease in Europe: A meta-analysis. Neurologia. 2017;32:523-32.

- Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, Strooper DB, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, et al. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2016;388:505-17.

- Vos SJ, Verhey F, Frolich L, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Maier W, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of Alzheimer's disease at the mild cognitive impairment stage. Brain. 2015;138:1327-38.

- Jack CR, Therneau TM, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, et al. Prevalence of Biologically vs Clinically Defined Alzheimer Spectrum Entities Using the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association Research Framework. JAMA Neurol. 2019.

- Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Salmon DP. Alzheimer's Disease: Past, Present, and Future. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017;23:818-31.

- Bhardwaj D, Mitra C, Narasimhulu CA, Riad A, Doomra M, Parthasarathy S, et al. Alzheimer's Disease-Current Status and Future Directions. J Med Food. 2017;20:1141-51.

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:1-16.

- Lee KY. Pathophysiology of age-related hearing loss (peripheral and central). Korean J Audiol. 2013;17:45-9.

- Moualed D, Humphries J, Ramsden JD. Cochlear dead regions: Using the Threshold Equalising Noise (TEN) test to improve the assessment of potential cochlear implant candidates-The Oxford experience. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018.

- Homans NC, Metselaar RM, Dingemanse JG, van der Schroeff MP, Brocaar MP, Wieringa MH, et al. Prevalence of age-related hearing loss, including sex differences, in older adults in a large cohort study. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:725-30.

- Salvi R, Ding D, Jiang H, Chen GD, Greco A, Manohar S, et al. Hidden Age-Related Hearing Loss and Hearing Disorders: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Hearing Balance Commun. 2018;16:74-82.

- Ralli M, Balla MP, Greco A, Altissimi G, Ricci P, Turchetta R, et al. Work-Related Noise Exposure in a Cohort of Patients with Chronic Tinnitus: Analysis of Demographic and Audiological Characteristics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9).

- Ralli M, Salvi RJ, Greco A, Turchetta R, De Virgilio A, Altissimi G, et al. Characteristics of somatic tinnitus patients with and without hyperacusis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188255.

- Ralli M, Greco A, De Vincentiis M, Sheppard A, Cappelli G, Neri I, et al. Tone-in-noise detection deficits in elderly patients with clinically normal hearing. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40:1-9.

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Synaptopathy in the noise-exposed and aging cochlea: Primary neural degeneration in acquired sensorineural hearing loss. Hear Res. 2015;330:191-9.

- Liberman MC, Kujawa SG. Cochlear synaptopathy in acquired sensorineural hearing loss: Manifestations and mechanisms. Hear Res. 2017;34:138-47.

- Hardy CJ, Marshall CR, Golden HL, Clark CN, Mummery CJ, Griffiths TD, et al. Hearing and dementia. J Neurol. 2016;263:2339-54.

- Liu CM, Lee CT. Association of Hearing Loss with Dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198112.

- Deal JA, Betz J, Yaffe K, Harris T, Purchase HE, Satterfield S, et al. Hearing Impairment and Incident Dementia and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults: The Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:703-9.

- Davies HR, Cadar D, Herbert A, Orrell M, Steptoe A. Hearing Impairment and Incident Dementia: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2074-81.

- Peracino A. Hearing loss and dementia in the aging population. Audiol Neurootol. 2014;19:6-9.

- Ford AH, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L, Almeida OP. Hearing loss and the risk of dementia in later life. Maturitas. 2018;112:1-11.

- Taljaard DS, Olaithe M, Brennan-Jones CG, Eikelboom RH, Bucks RS. The relationship between hearing impairment and cognitive function: a meta-analysis in adults. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41:718-29.

- Swords GM, Nguyen LT, Mudar RA, Llano DA. Auditory system dysfunction in Alzheimer disease and its prodromal states: A review. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;44:49-59.

- Hallberg LR, Hallberg U, Kramer SE. Self-reported hearing difficulties, communication strategies and psychological general well-being (quality of life) in patients with acquired hearing impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:203-12.

- Uhlmann RF, Larson EB, Koepsell TD. Hearing impairment and cognitive decline in senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:207-10.

- Uhlmann RF, Larson EB, Rees TS, Koepsell TD, Duckert LG. Relationship of hearing impairment to dementia and cognitive dysfunction in older adults. JAMA. 1989;261:1916-9.

- Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, Xue QL, Harris TB, Purchase-HE, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:293-9.

- Thomson RS, Auduong P, Miller AT, Gurgel RK. Hearing loss as a risk factor for dementia: A systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:69-79.

- Gurgel RK, Ward PD, Schwartz S, Norton MC, Foster NL, Tschanz JT. Relationship of hearing loss and dementia: a prospective, population-based study. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35:775-81.

- Lin FR, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, An Y, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:763-70.

- Mick P, Kawachi I, Lin FR. The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150:378-84.

- Shankar A, Hamer M, Munn A, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:161-70.

- Cardin V. Effects of Aging and Adult-Onset Hearing Loss on Cortical Auditory Regions. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:199.

- Fortunato S, Forli F, Guglielmi V, Corso E, Paludetti G, Berrettini S, et al. A review of new insights on the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline in ageing. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016;36:155-66.

- Yesavage JA, Ohara R, Kraemer H, Noda A, Taylor JL, Ferris S, et al. Modelling the prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:281-6.

- Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Seripa D, Imbimbo BP, Capozzo R, Quaranta N, et al. Age-related hearing impairment and frailty in Alzheimer's disease: interconnected associations and mechanisms. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:113-14.

- Lin FR, Ferrucci L, An Y, Goh JO, Doshi J, Metter EJ, et al. Association of hearing impairment with brain volume changes in older adults. Neuroimage. 2014;90:84-92.

- Osler M, Christensen GT, Mortensen EL, Christensen K, Garde E, Rozing MP. Hearing loss, cognitive ability, and dementia in men age 19-78 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:125-30.

- Martini A, Castiglione A, Bovo R, Vallesi A, Gabelli C. Aging, cognitive load, dementia and hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol. 2014;191:2-5.

- Chang M, Kim HJ, Mook-Jung I, Oh SH. Hearing loss as a risk factor for cognitive impairment and loss of synapses in the hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2019;372:1120-69.

- Shen Y, Ye B, Chen P, Wang Q, Fan C, Shu Y, et al. Cognitive Decline, Dementia, Alzheimer's Disease and Presbycusis: Examination of the Possible Molecular Mechanism. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:394.

- Xue T, Wei L, Zha DJ, Qiu JH, Chen FQ, Qiao L, et al. miR-29b overexpression induces cochlear hair cell apoptosis through the regulation of SIRT1/PGC-1alpha signalling: Implications for age-related hearing loss. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:1387-94.

- Hill K, Yuan H, Wang X, Sha SH. Noise-Induced Loss of Hair Cells and Cochlear Synaptopathy are Mediated by the Activation of AMPK. J Neurosci. 2016;36:7497-510.

- Kumar R, Chaterjee P, Sharma PK, Singh AK, Gupta A, Gill K, et al. Sirtuin: A promising serum protein marker for early detection of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61560.

- Won JS, Im YB, Kim J, Singh AK, Singh I. Involvement of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) in neuronal amyloidogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:487-91.

- Picciotti PM, Fetoni AR, Paludetti G, Wolf FI, Torsello A, Troiani D, et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) expression in noise-induced hearing loss. Hear Res. 2006;214:76-83.

- Kalaria RN, Cohen DL, Prem kumar DR, Nag S, LaManna JC, Lust WD. Vascular endothelial growth factor in Alzheimer's disease and experimental cerebral ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;62:101-5.

- Golden HL, Nicholas JM, Yong KX, Downey LE, Schott JM, Mummery CJ, et al. auditory spatial processing in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2015;138:189-202.

- Gates GA, Anderson ML, Curry SM, Feeney MP, Larson EB. Central auditory dysfunction as a harbinger of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:390-5.

- Golob EJ, Ringman JM, Irimajiri R, Bright S, Schaffer B, Medina LD, et al. Cortical event-related potentials in preclinical familial Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1649-55.

- Hardy CJD, Frost C, Sivasathia SH, Johnson JCS, Agustus JL, Bond RL, et al. Findings of Impaired Hearing in Patients with Nonfluent/Agrammatic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:607-11.

- Gates GA, Cobb JL, Linn RT, Rees T, Wolf PA, Dagostino RB. Central auditory dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia in older people. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:161-7.

- Nguyen MF, Bonnefoy M, Adrait A, Gueugnon M, Petitot C, Collet L, et al. Efficacy of Hearing aids on the Cognitive Status of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Hearing Loss: A Multi-center Controlled Randomized Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:123-37.

- Villeneuve A, Hommet C, Aussedat C, Lescanne E, Reffet K, Bakhos D. Audiometric evaluation in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:151-7.

- Durrant JD, Palmer CV, Lunner T. Analysis of counted behaviours in a single-subject design: modelling of hearing-aid intervention in hearing-impaired patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:31-8.

- Palmer CV, Adams SW, Durrant JD, Bourgeois M, Rossi M. Managing hearing loss in a patient with Alzheimer disease. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998;9:275-84.

- Van Knijff EC, Coene M, Govaerts PJ. Speech understanding in noise in elderly adults: the effect of inhibitory control and syntactic complexity. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2018;53:628-42.

- Clark CN, Warren JD. Emotional caricatures in fronto-temporal dementia. Cortex. 2016;76:134-6.

- Griffiths TD. Musical hallucinosis in acquired deafness. Phenomenology and brain substrate. Brain. 2000;123:2065-76.

- Di Stadio A, Dipietro L, Ricci G, Della Volpe A, Minni A, Greco A, et al. Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, Hyperacusis, and Diplacusis in Professional Musicians: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1-10.

- Aazh H, Moore BC, Lammaing K, Cropley M. Tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a UK National Health Service audiology department: Patients' evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments. Int J Audiol. 2016;55:514-22.

- Mahoney CJ, Rohrer JD, Goll JC, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD. Structural neuro-anatomy of tinnitus and hyperacusis in semantic dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:1274-8.

- Kwak C, Kim S, Lee J, Seo Y, Kong T, Han W. Speech Perception and Gap Detection Performance of Single-Sided Deafness under Noisy Conditions. J Audiol Otol. 2019.

- Westerhausen R, Kompus K. How to get a left-ear advantage: A technical review of assessing brain asymmetry with dichotic listening. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59:66-73.

- Rahman TT, Mohamed ST, Albanouby MH, Bekhet HF. Central auditory processing in elderly with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:304-8.

- Ralli M, Greco A, Altissimi G, Turchetta R, Longo L, Aguanno V, et al. Vestibular Schwannoma and Ipsilateral Endolymphatic Hydrops: An Unusual Association. Int Tinnitus J. 2017;21:128-32.

- Martuza RL, Parker SW, Nadol JB, Davis KR, Ojemann RG. Diagnosis of cerebellopontine angle tumors. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:177-213.

- Sugiura S, Uchida Y, Nakashima T, Nishita Y, Tange C, Ando F, et al. Association between cerumen impaction, cognitive function and hearing in Japanese elderly. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2012;49:325-9.

- Sugiura S, Yasue M, Sakurai T, Sumigaki C, Uchida Y, Nakashima T, et al. Effect of cerumen impaction on hearing and cognitive functions in Japanese older adults with cognitive impairment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:56-61.

- Allen NH, Burns A, Newton V, Hickson F, Ramsden R, Rogers J, et al. The effects of improving hearing in dementia. Age Ageing. 2003;32:189-93.

References

1Department of Sense Organs, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

2Department of Otolaryngology, University of Perugia, Italy

3Department of Biology, CNR Institute of Cell Biology and Neurobiology, Italy

4Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Send correspondence to: Arianna Di Stadio Department of Otolaryngology, University of Perugia, Italy E-mail: mailto:ariannadistadio@hotmail.com Tel: +39-333-820-0853.

Citation: Ralli M, Gilardi A, Stadio AD, Severini C,Salzano FA, Greco A. Hearing loss and Alzheimer’s disease: A Review. Int Tinnitus J. 2019;23(2):79-85.

Paper submitted to the ITJ-EM (Editorial Manager System) on August 12, 2019; and Accepted on August 23, 2019